Definition of feedback and feedback models

“Feedback is a gift” is a well-known saying. Some people may be suspicious of this phrase – until they engage with the work of Professor Carol Dweck (Dweck, 2006; Yeager & Dweck, 2012) which may lead to a transformation in their thinking about our ability to learn. From reading the books of Norman Doidge (2007, 2016) and Oliver Sacks (1994, 2007) I was already familiar with neuroplasticity; that as adults we can still make new neural pathways. It takes adults a while to make new pathways, about three months to re-wire our neurons. The change will feel uphill at the start as the brain is working against the established thought processes. Over time it will become easier until we are able to go in the direction of our newly trained neural pathways

Feedback is a fitting topic to discuss at the start of a new year and school term. It’s a time when we focus on New Year’s Resolutions, what we want to change and how we will change. Dylan Wiliam in his book Leadership [for] Teacher Learning: Creating a Culture where All Teachers Improve So that All Students Succeed summarises key findings from Dweck (a book my co-author, Ollie Lovell recommended to me and I am loving – here is a podcast with Ollie and Dylan Wiliam about his book if you want to hear more):

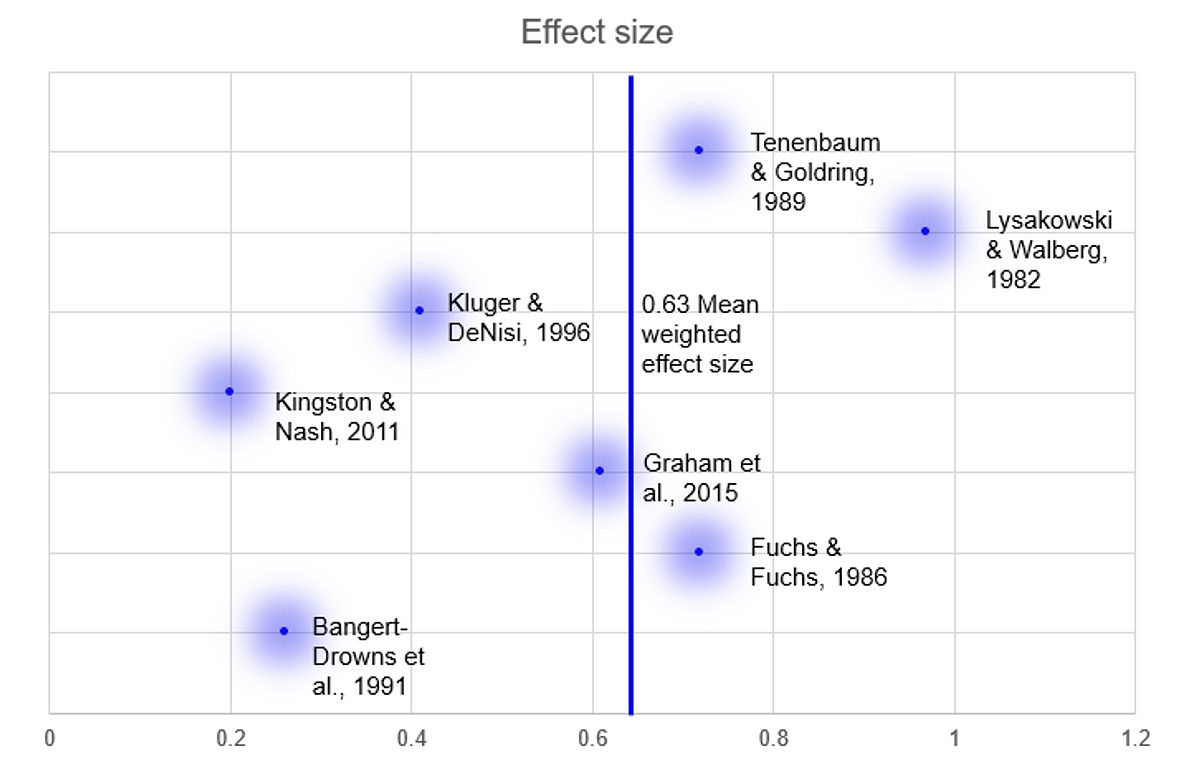

Important to encouraging adult and student change is high quality feedback. Feedback that directs attention to the self (e.g. praise etc) is far less effective and can even produce a negative impact on learning (Kluger & DeNisi, 1996). This is why the study from Kluger and DeNisi (1996) shows a relatively low weighted mean effect size in comparison to some other studies within the Teaching & Learning Toolkit as shown in Figure 1. They found that a third of the studies (they looked at 607 effect sizes) included within their meta-analysis on feedback interventions had a negative impact on student learning, with an effect size of 0.41. The feedback interventions that did have a positive impact focused on cues that support learning and attracting attention to feedback-standard discrepancies.

Another study from Lysakowski and Walberg (1982) just looked at cues, participation and corrective feedback on learning. You can see this study as an outlier to the far right of the graph in Figure 1, with and effect size of 0.97. Some examples of cues are thumbs up or down to indicate understanding (Earp, 2018).

Figure 1: Range of effect sizes within the Teaching & Learning Toolkit references

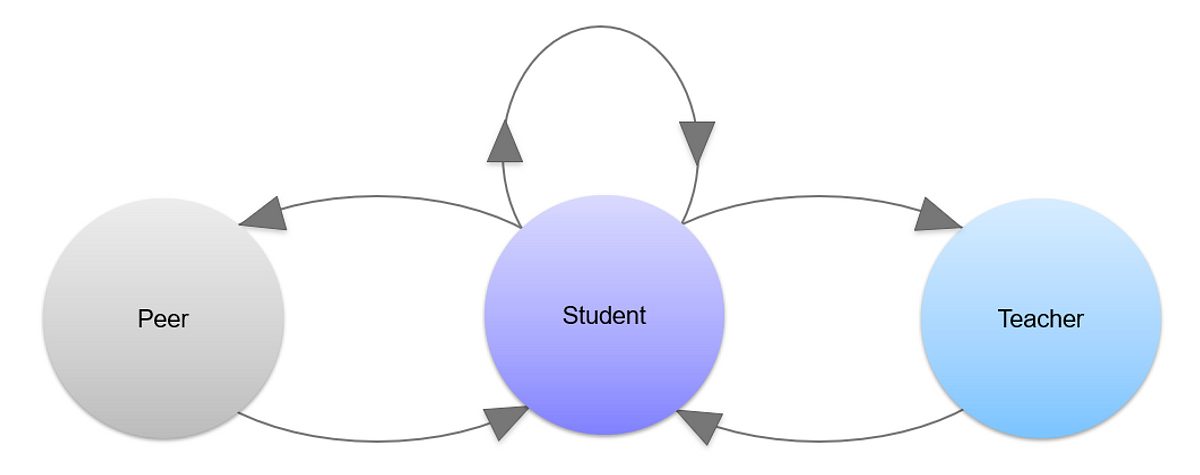

Ollie Lovell is a teacher and Coordinator of Mathematics at Sunshine College in Victoria and sees classroom feedback in action on a daily basis. Ollie shares his conceptual model of feedback that demonstrates how the above theories can play out in the real world. This model includes the follow types of feedback:

- Student to peer

- Student to teacher

- Student self-reflection

- Teacher to student feedback.

Figure 2: A model for feedback types within the classroom

Student to peer feedback

Students providing feedback to a peer can be a fantastic way to draw their attention to success criteria. One easy way to do this is via a ‘pre-flight checklist’ (Wiliam, 2011, p. 163). For a task in which students must adhere to a clear set of specifications, such as a science report requiring a hypothesis, method, results, etc, a teacher can pair students up and require that before submission, they must be signed off by a buddy, who uses a checklist to ensure the original student has ticked all of the boxes. Weight can be added to this task whereby if a checking student approves of a task that hasn’t checked all the boxes, the checker rather than the submitter can be the one who is penalised.

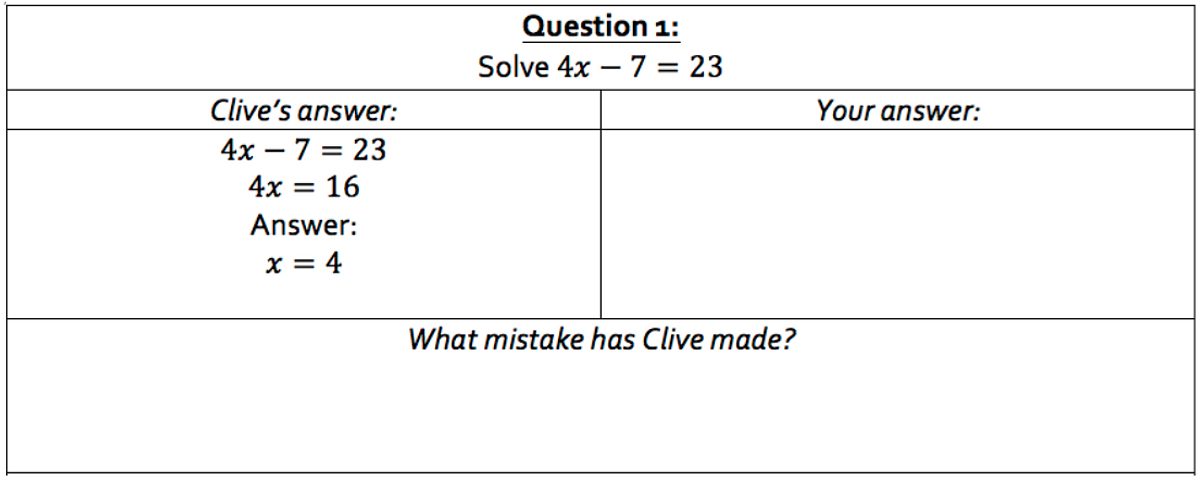

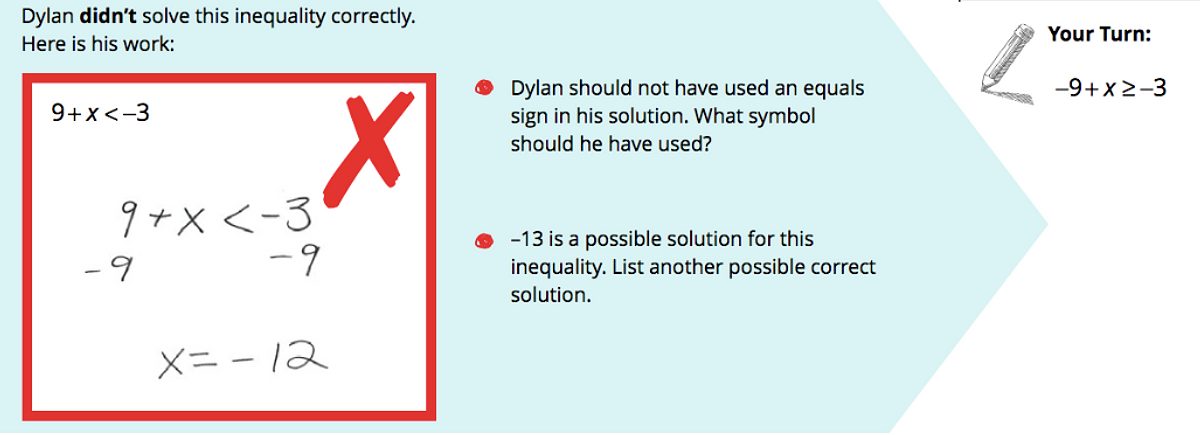

Another approach that is somewhat of a modification of the ‘student to peer’ feedback approach is asking students to consider an incorrectly completed question. In mathematics, this can be done several ways but two good resources are Clumsy Clive and Algebra by Example. The following two images come from these sites, and it can be seen how such a task can draw students’ attention to common errors and provide a stimulus for discussion and exploration of such errors.

Figure 3: An example of practising identifying common errors in mathematics from Clumsy Clive

Figure 4: An example of practising identifying common errors in mathematics from Algebra by Example

Student to teacher feedback

There are numerous ways to elicit student feedback on teachers, one of which I’ve written about in this blog here. The challenge with student feedback is its reliability. For example, some research (Clark, 1982) has demonstrated a negative correlation between students’ enjoyment of instructional methods and their achievement under certain conditions. That is ‘students often report enjoying the method from which they learn the least’ (Clark, 1982, p. 92). Keeping in mind this and other limitations (this podcast contains an excellent discussion of further limitations), it’s important that we do give students opportunities to feedback on teacher learning as it can still highlight ways for teachers to improve, as well as providing affective benefits and helps to build a school culture in which all participants are seen as learners.

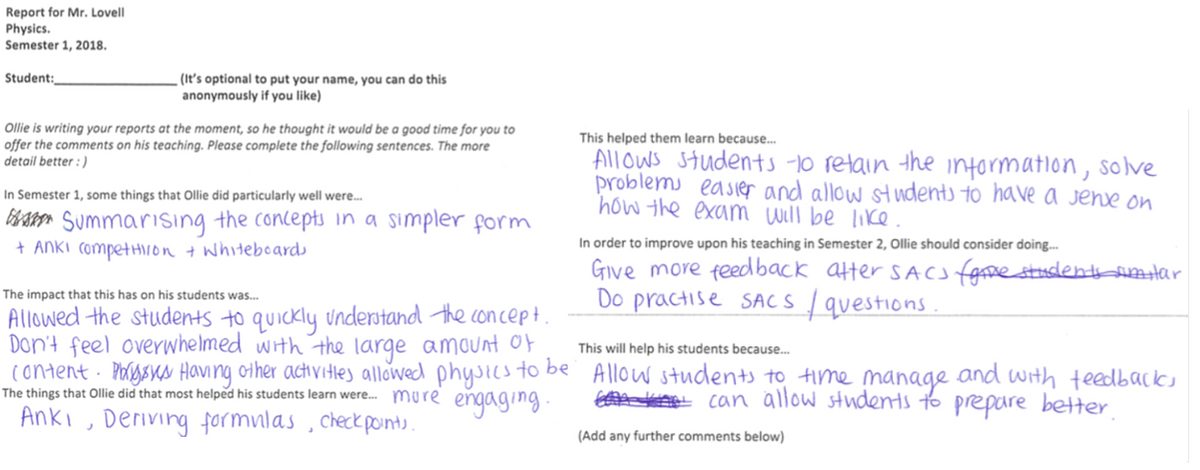

Building on this mindset of reciprocal learning and teaching, one novel way for students to feedback to teachers is to write a report. Here is one example:

Figure 5: An example of a report from a student to a teacher from Ollie’s classroom

The wording at the top of this task, ‘(teacher’s name) is writing your reports at the moment, so he thought it would be a good time for you to offer comments on his/her/their teaching…’ demonstrates a teacher’s willingness to learn, and listen to their class, and can help to break down traditional power structures which can hinder (but also sometimes aid) learning.

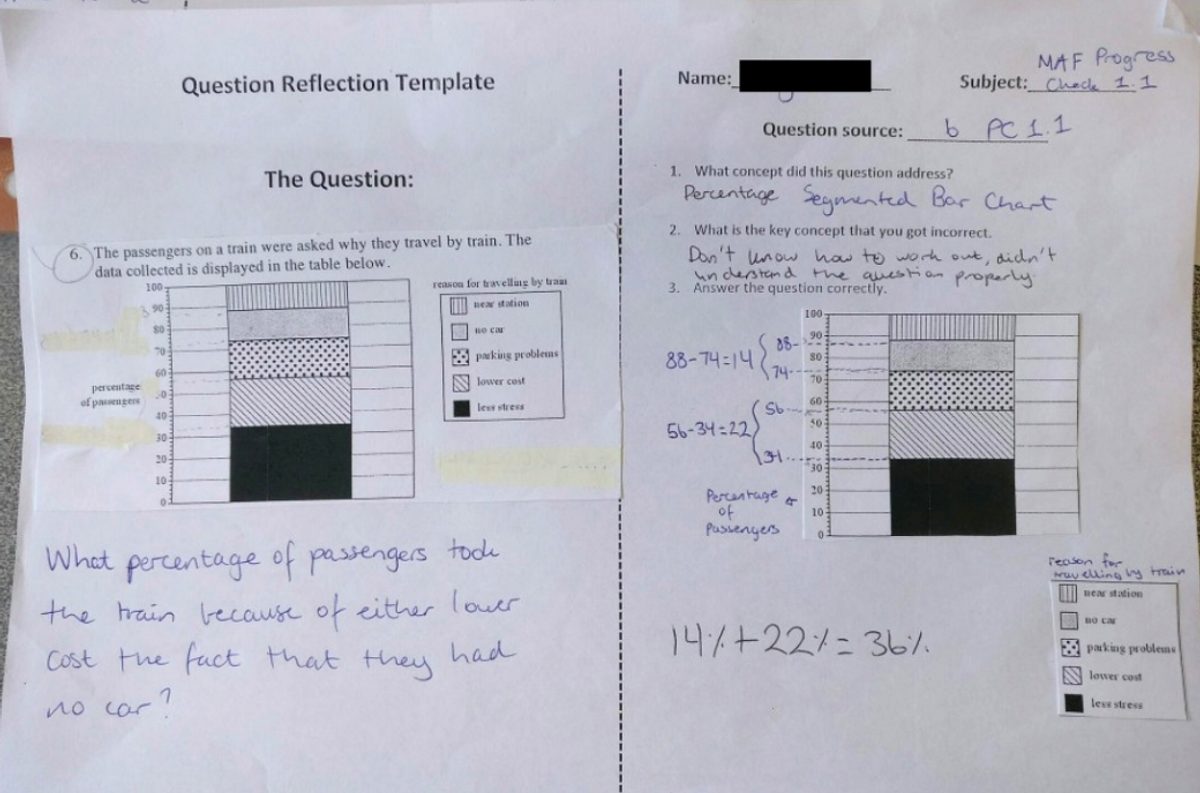

Student self-reflection

It is important for students to reflect upon what has and hasn’t gone well in their learning to date in order to ensure that desired knowledge and skills are reinforced, whereas incorrect approaches are not. One way to do this is using a scaffold to support student reflection. Such a scaffold can include questions such as ‘What was the question? What concept did it address?’ and ‘What is the mistake that you made?’, drawing students’ attention to the key question components. Below is a photograph of such a reflection.

Figure 6: An example of a question reflection template from Ollie’s classroom

One key factor to keep in mind here is the learning orientation that a student brings to such a task. Ron Ritchhart, in his book Creating Cultures of Thinking (Ritchart, 2015), draws the distinction between learning and work, exploring the language that is used in a work-oriented vs. a learning-oriented classroom:

If such a reflection is undertaken in a work oriented classroom, it can be just as useless as no reflection at all. However, if used as part of a learning oriented learning environment, such a scaffold can be a powerful tool to aid student learning.

Teacher to student feedback

Much has been written about teacher to student feedback. We know, for example, that feedback is more effective when it is specific, actionable and moves the learner forward. One way to do this is to offer feedback in a way that provides students with additional opportunities to practice the skills that need more work.

Many schools undertake ‘item analyses’ in response to, for example, mathematics tests. Teachers are asked to produce large spreadsheets with a row for each student, a column for each question on the test, and a mark in each cell indicating the students’ progress on each question.

This can be a powerful tool for diagnosis, but it has some limitations. Firstly, performance does not always indicate learning. Said another way, just because a student can answer a question on factorization today does not mean they’ll be able to answer that same question a week from now. Secondly, the question sample is often too small to be able to draw inferences about a given student’s ability with respect to the skill in question. And finally, such an approach takes a lot of teacher time and can unduly add to workload.

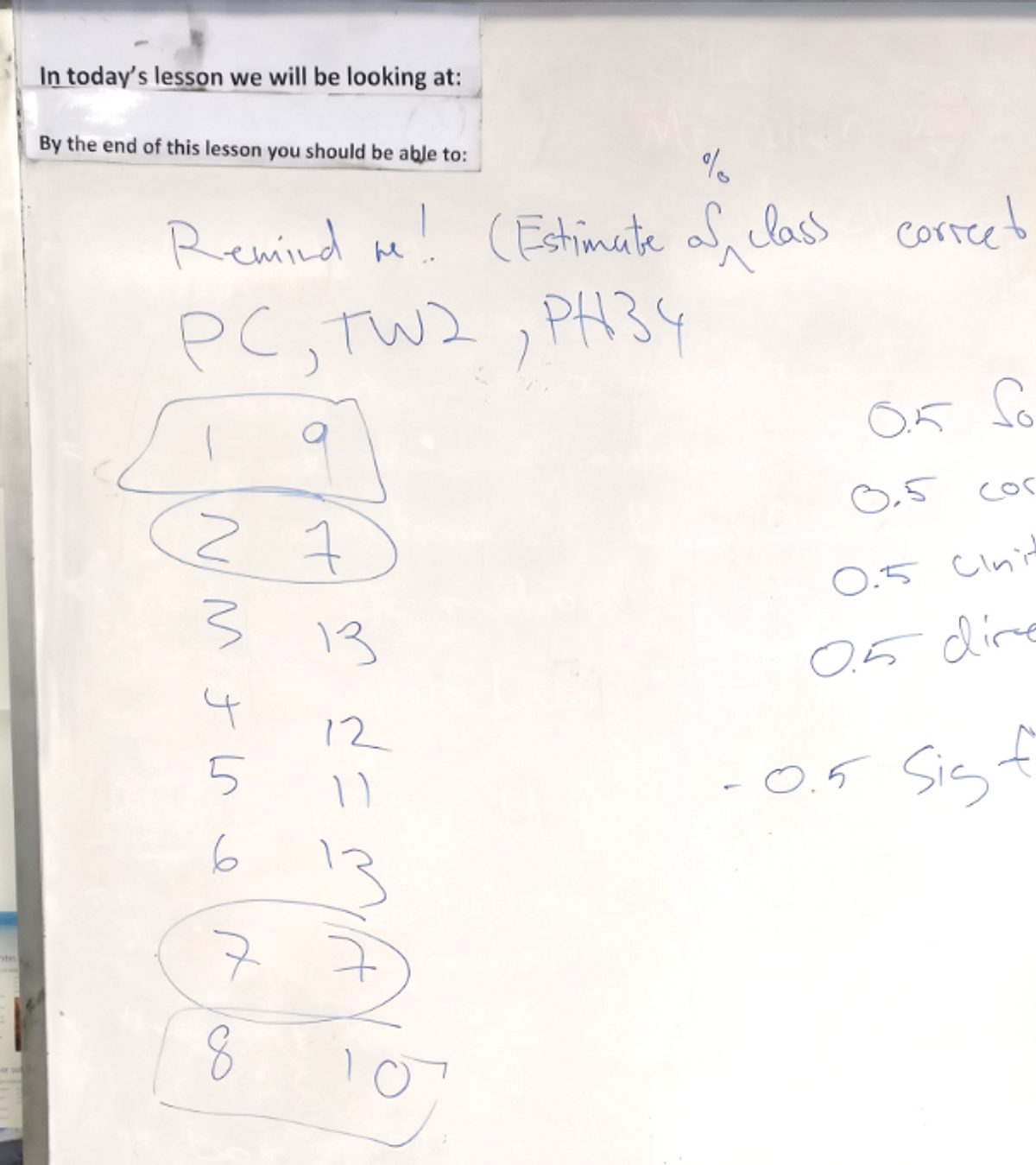

A quick and effective whole-class approach to feedback following a short quiz could run as follows. At the end of a quiz, a teacher can write the question numbers up on the board and say, for example, ‘Raise your hand if you got question 1 correct’*, then mark the number of students who answered it correctly and move on to the next question.

What is produced is a tally, such as the one pictured below in Figure 7.

Figure 7: An example of a quiz tally from Ollie’s classroom

This also allows a teacher quickly (within less than a minute), identify weak points for the whole class, and revisit these concepts in future instruction, homework tasks, or in future quizzes.

*Asking students to raise their hand if they were correct provides them with an opportunity to celebrate their success rather than asking those who answered incorrectly to raise their hands.

Conclusion

Feedback is indeed a gift if it is both given and received. It is a gift that recognises that we can grow and become our better selves through graciously accepting feedback from our students, so we can become more effective at helping our students learn. It’s a gift that helps our students achieve and learn how they can give feedback to each other and self-reflect on their own progress. In teaching our students how to give and receive feedback and demonstrating our ability to grow in response to feedback we are living examples of a growth mindset.

Authors

Ollie Lovell is a teacher and Senior Mathematics Coordinator at Sunshine College. If you want to engage with more of Ollie’s work you can sign up to his weekly email, read his blogs (ollielovell.com) or listen to his podcast (ollielovell.com/podcast).

Dr Tanya Vaughan is an Associate Director at Evidence for Learning. She is responsible for the product development, community leadership and strategy of the Toolkit.

References

Clark, R. E. (1982). Antagonism between achievement and enjoyment in ATI studies. Educational psychologist, 17(2), 92 – 101.

Doidge, N. (2007). The brain that changes itself: Stories of personal triumph from the frontiers of brain science: Penguin.

Doidge, N. (2016). The brain’s way of healing: Remarkable discoveries and recoveries from the frontiers of neuroplasticity: Penguin Books.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success: Random House Incorporated.

Earp, J. (2018). Collecting and acting on student feedback. Teacher. Retrieved from https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/articles/collecting-and-acting-on-student-feedback

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological bulletin, 119(2), 254.

Lysakowski, R. S., & Walberg, H. J. (1982). Instructional effects of cues, participation, and corrective feedback: A quantitative synthesis. American educational research journal, 19(4), 559 – 572.

Ritchhart, R. (2015). Creating cultures of thinking: The 8 forces we must master to truly transform our schools: John Wiley & Sons.

Sacks, O. (1994). The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. In: Summit: New.

Sacks, O. (2007). Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain. New York: Random House.

Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment: Solution Tree Press.

Wiliam, D. (2016). Leadership [for] Teacher Learning: Creating a Culture where All Teachers Improve So that All Students Succeed. Moorabbin, Victoria: Hawker Brownlow.

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational psychologist, 47(4), 302 – 314.