As global evidence shows, feedback has a significant impact on learning, contributing a gain of as much as eight months’ worth of learning progress in a year when implemented well (Education Endowment Foundation, 2017). However, no in-depth studies have been completed in Australia, although a few have been conducted in New Zealand (Evidence for Learning in collaboration with Melbourne Graduate School of Education, 2017).

In this blog, I’m going to discuss how we start to develop an Australian evidence-base in implementing effective feedback, and Ollie Lovell, Senior Maths Coordinator at Sunshine College in Victoria and creator of education blog ollielovell.com and ERRR podcastwill share his own feedback teaching methods.

Identifying this lack of local research helped drive Evidence for Learning to ask the question

Earlier in June, Evidence for Learning in partnership with the Australian Institute of Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) released new feedback Implementation materials (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2014) with two main objectives:

- Answering this question; and

- Helping educators know what works, why and importantly, how.

With over 11,000 visits to the site since their release, they’re proving to be a well accessed resource to provide relevant, evidence-informed and practical support to guide implementation and measurement for educators.

Putting evidence into action

I have been fortunate to be facilitating workshops across Australia, including the Northern Territory, Western Australia, New South Wales, Queensland and Victoria, with these feedback materials in the months leading up to and after their release. A table adapted for the workshops from the Spotlight: Reframing feedback to improve teaching and learning, has been consistently well received by educators.

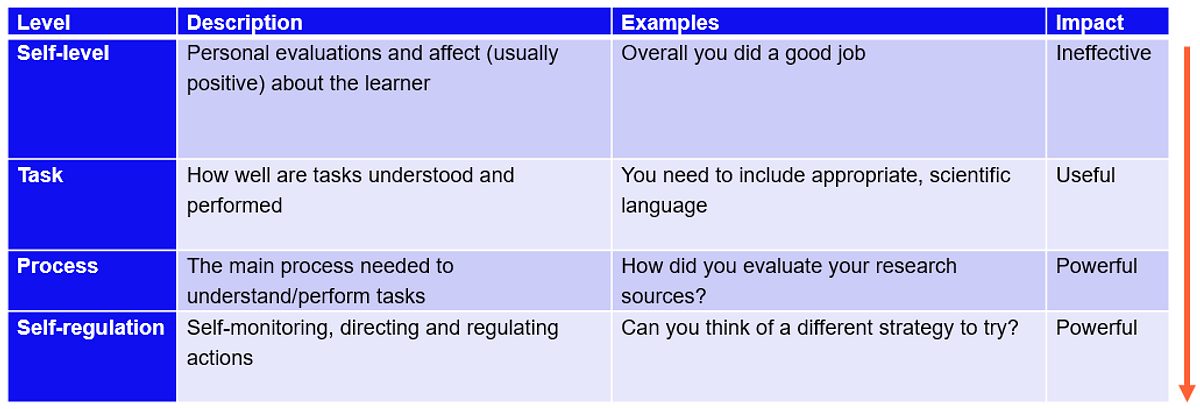

Table 1 below outlines the different levels at which feedback can be provided, and the relative effectiveness of targeting feedback at the level of self, task, process and self-regulation.

Table 1: Feedback levels and their impact

In my introduction to feedback within the workshops, I always refer to the importance of trust. Trust facilitates an environment where students can take the feedback and make changes to their work. I like to draw on an insightful quote from Dylan Wiliam:

Whilst the feedback resources were in development, I was fortunate to meet up with Ollie Lovell, Senior Mathematics Coordinator at Sunshine College in Victoria. Ollie showed me the feedback form he had developed to better gather feedback from his students.

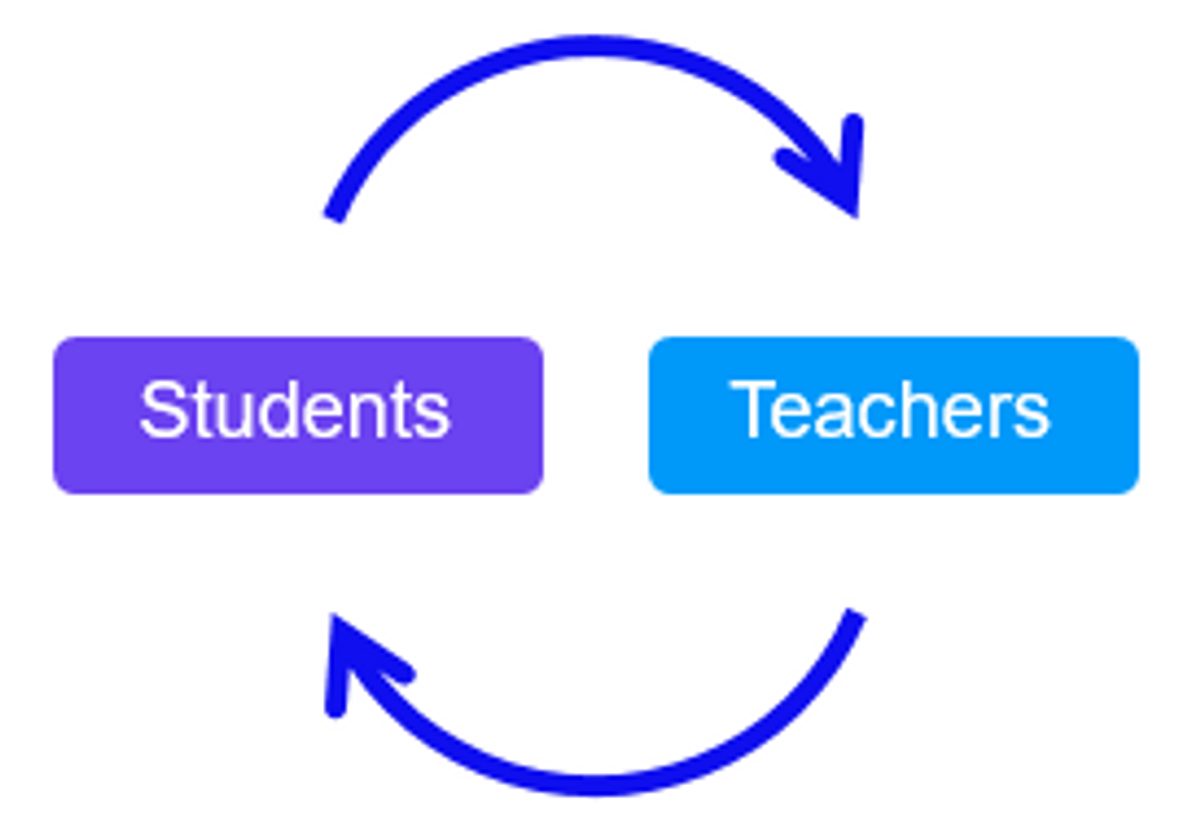

Feedback in the Sunshine College Mathematics department flows in two directions, feedback to students, and feedback to teachers.

This is in line with the knowledge that ‘the biggest effects on student learning occur when teachers become learners of their own teaching, and when students become their own teachers.’ (Hattie, 2009, p. 22)

Here’s one way teachers can give effective feedback to students

Progress Checks (PCs, mini tests, max 15 minutes) are held weekly in order to make use of the retrieval effect, whereby repeatedly retrieving information from memory aids in strengthening memory for that information (Roediger & Butler, 2011). The first feedback on PCs is given by the teacher. At the process level this is via the teacher modelling solutions immediately after PCs are completed, with students self-marking.

Feedback is given in this way as we know that for maximum efficacy, feedback should be immediate, and ‘pupils should be trained in self- assessment so that they can understand the main purposes of their learning and thereby grasp what they need to do to achieve.’ (Black & Wiliam, 2010).

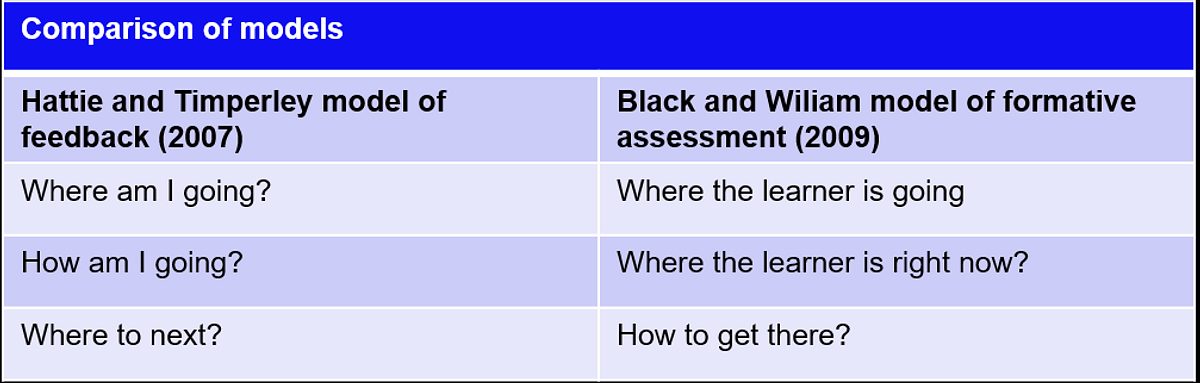

The second feedback on PCs is at the self-regulation level, with students undertaking a structured PC reflection. This reflection follows the three steps of effective feedback as summarised in Spotlight: Reframing feedback to improve teaching and learning (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2017, p. 6).

Table 2: Comparison of feedback models

Students are required to reflect upon three questions that follow these two models. They are asked to identify one (or more) questions that they got incorrect on their PC, and answer the following questions in relation to it.

- What concept did this question address? Where am I going? Prompting students to categorise the question, better organising it in their mental planning

- Which key concept did you get incorrect? How am I going? Students explicitly point out the mistake made.

- How to do it next time. Where to next? Students provide a pathway to a correct response.

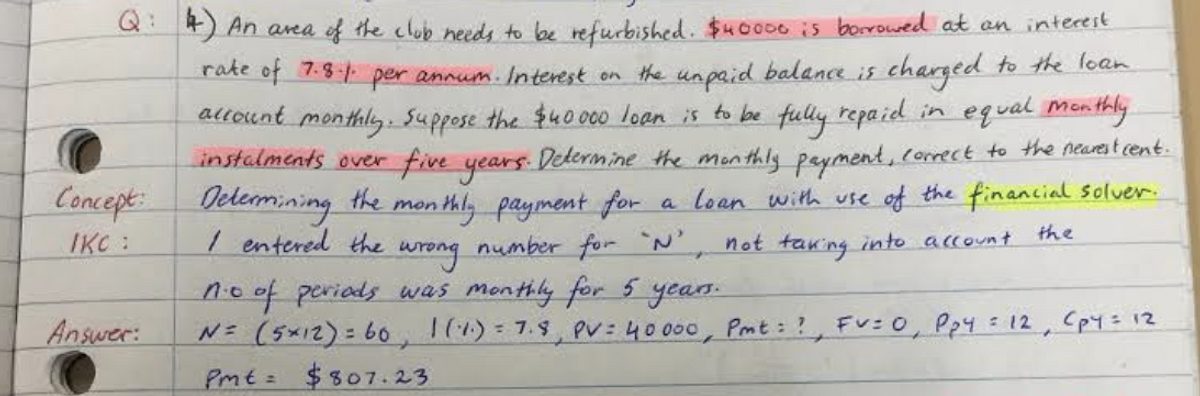

In my classes, each week I highlight the ‘PC reflection of the week’, I project it onto the board as an example for other students, and explicitly point out what made it a high quality reflection. These reflections need not be long. Here’s a picture of a recent PC reflection by one of my students, for which I awarded ‘PC reflection of the week’.

This solution pertains to the use of a computer algebra system (CAS) calculator, the variables defined are calculator inputs.

In addition to allowing me to highlight key characteristics of good student self-reflection, this also allows me to reward students for effort (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2014; Dweck, 2007) Any student can achieve the PC reflection of the week award, irrespective of their current level of achievement, and I keep a record of who has been awarded to ensure that a variety of high quality student work is acknowledged.

How can students give feedback to teachers?

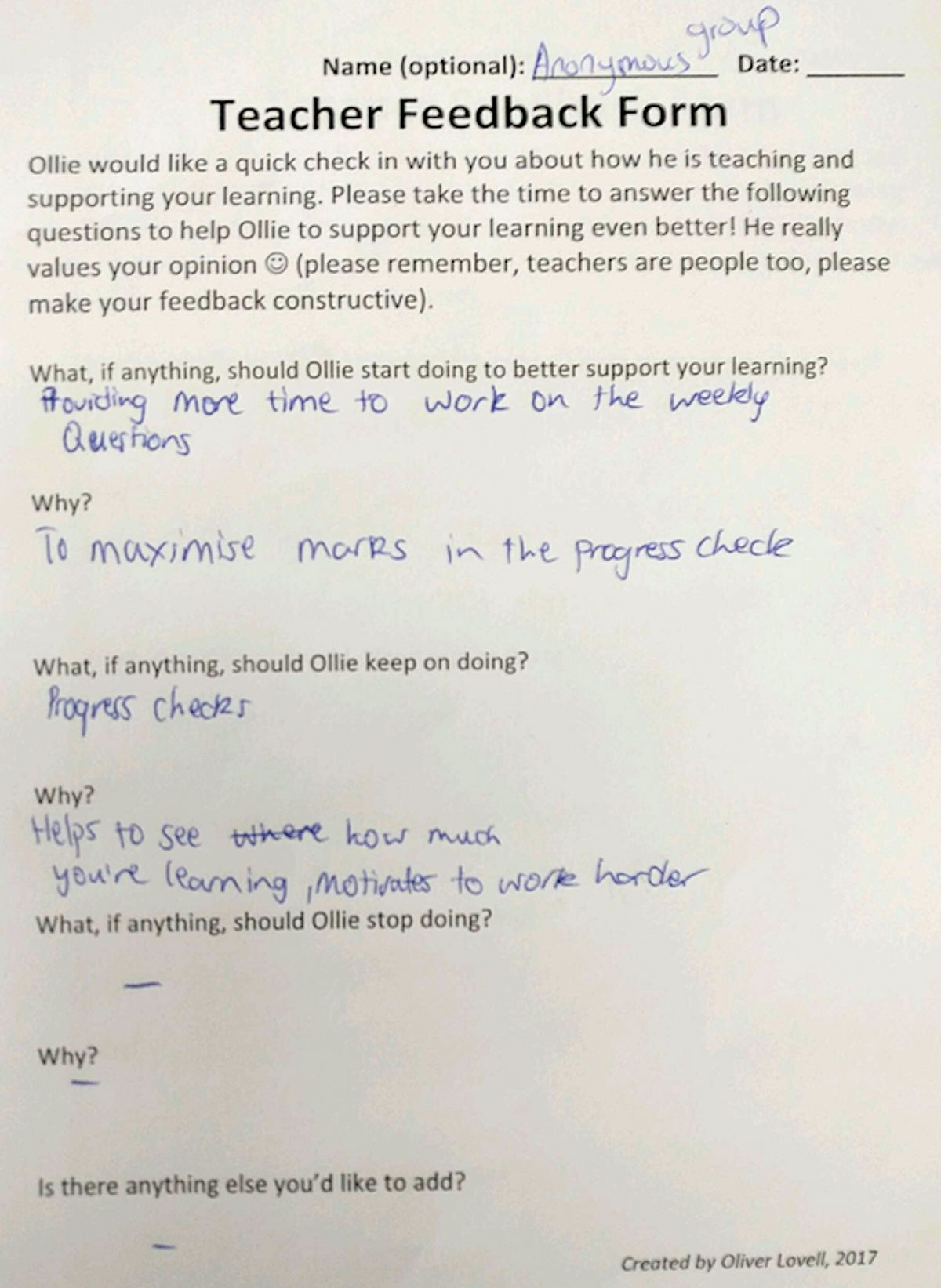

Above is the text that begins the Sunshine College Senior Mathematics student-feedback form. Ultimately, students are the ones most influenced by our instructional choices. They have specific expertise when it comes to reflecting upon what is and isn’t working in the classroom. Beyond this, the process of asking students for their opinions is an invaluable step to building strong, respectful and collaborative relationships with them.

Initial iterations of the SC senior maths student-feedback form asked three simple questions:

- What should this teacher keep doing and why?

- What should this teacher start doing and why?

- What should this teacher stop doing and why?

Whilst a great starting point, it was found that student responses were not specific enough to inform focused areas of improvement for teachers.

Example of initial iteration of student feedback form.

In response to this, the team turned to the paper by Coe and colleagues entitled What makes great teaching? We used the first four of six ‘common components suggested by research that teachers should consider when assessing teaching quality.’ (Coe et al., 2014, p. 2). These are the components rated as having ‘strong’ or ‘moderate’ evidence of impact on student outcomes, and they’re also the components with observable outcomes in the classroom (5 and 6 are ‘Teacher Beliefs’ and ‘Professional Behaviours’, which encapsulate practices like reflecting on praxis and collaborating with colleagues).

Each of these four selected components were then deconstructed into constituent questions. Against each, students give a rating from 1‑disagree strongly, to 7‑agree strongly. These questions, along with additional open-ended questions (in italics) are, available in a live google form available here.

As I write this, we are in the process of collecting student answers to this survey for the first time. As such, it’s too early to comment on the effectiveness of this new iteration of our student-feedback survey, but I’ll blog about the process and its effectiveness once we have results and have had some time to analyse and reflect upon them.

I hope this article has provided a stimulating example of some ways in which we’re striving to implement evidence-informed feedback processes at Sunshine College Senior Campus.

If you have any thoughts, comments or reflections, please share them with us on twitter @E4Ltweets@ollie_lovell@tvaughanEdu.

References

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2014). Feedback.Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/feedback/

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2017). Reframing feedback to improve teaching and learning.Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/docs/default-source/research-evidence/spotlight/spotlight-feedback.pdf

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2010). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(1), 81 – 90.

Coe, R., Aloisi, C., Higgins, S., & Major, L. E. (2014). What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research.

Dweck, C. S. (2007). The perils and promises of praise. ASCD, 65(2), 34 – 39.

Education Endowment Foundation. (2017). Evidence for Learning Teaching & Learning Toolkit: Education Endowment Foundation. Feedback. Retrieved from http://evidenceforlearning.org.au/toolkit/feedback/

Evidence for Learning in collaboration with Melbourne Graduate School of Education. (2017). Feedback: Australasian Research Summaries. Retrieved from http://www.evidenceforlearning.org.au/australasian-research-summaries/feedback

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analysis relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in cognitive sciences, 15(1), 20 – 27.

Wiliam, D. (2016). The secret of effective feedback. Educational Leadership, 73(7), 10 – 15.

*Cover photo credit: David Turner, Director of Professional Learning, Queensland Association of State School Principals