Introduction to the ‘evidence for impact’ blog series

With the new year well underway, schools and early learning settings across Australia are grappling with the past and present impacts of the pandemic. This challenging context provides an opportunity for instructional leaders to use a strong evidence base to focus upon targeted and manageable actions that support learning and wellbeing.

The impacts of the pandemic on children and young people can be highly variable, with significant differences to be expected across contexts, cohorts and circumstances. Furthermore, there is ongoing potential for additional disruption of learning and development due to isolation requirements for both educators and children who develop Covid-19 or are close contacts of those who do.

The first blog of the series is about metacognition. You can read more about upcoming blogs in the series here.

Metacognition is a high-impact, low-cost strategy that may be of use to instructional leaders to support student learning at this time.

What is metacognition?

Put simply, metacognition is about students’ ability to monitor, purposefully direct and review their learning. Effective metacognitive strategies get learners to think about their own learning more explicitly, usually by teaching them to set goals, and monitor and evaluate their own academic progress.

There are some persistent myths about metacognition that can hinder efforts to support its development. It is clear from research that:

- Metacognition is specific to the task being undertaken and is best developed through practice on specific tasks and not as a general skill.

- Age is no barrier, with children as young as three able to engage in a wide range of metacognitive behaviours.

- Metacognition is not higher in the hierarchy than other cognitive activities such as remembering knowledge.

- There is little evidence of the benefit of teaching metacognitive approaches in separate ‘learning to learn’ or ‘thinking skills’ sessions.

Metacognition is intrinsically linked with cognition and motivation. It is impossible to be metacognitive without having different cognitive strategies to draw on and possessing the motivation and perseverance to tackle problems and apply these strategies.

What does the research say about metacognition?

Evidence from the Teaching & Learning Toolkit suggests that the use of metacognition and self-regulation has consistently high levels of impact. It can lead to learning gains of +7 months over the course of a year, when used well. The Toolkit evidence has a high level of security and implementing metacognition is relatively low in cost.

The Guidance Report on Metacognition & Self-Regulated Learning has seven key recommendations that are unpacked in detail. These are most likely to be successful when implemented strategically over the longer term within a supportive culture. To address the challenges of this moment, we will briefly zoom in on two recommendations that can be acted upon now.

Explicitly teach students metacognitive strategies

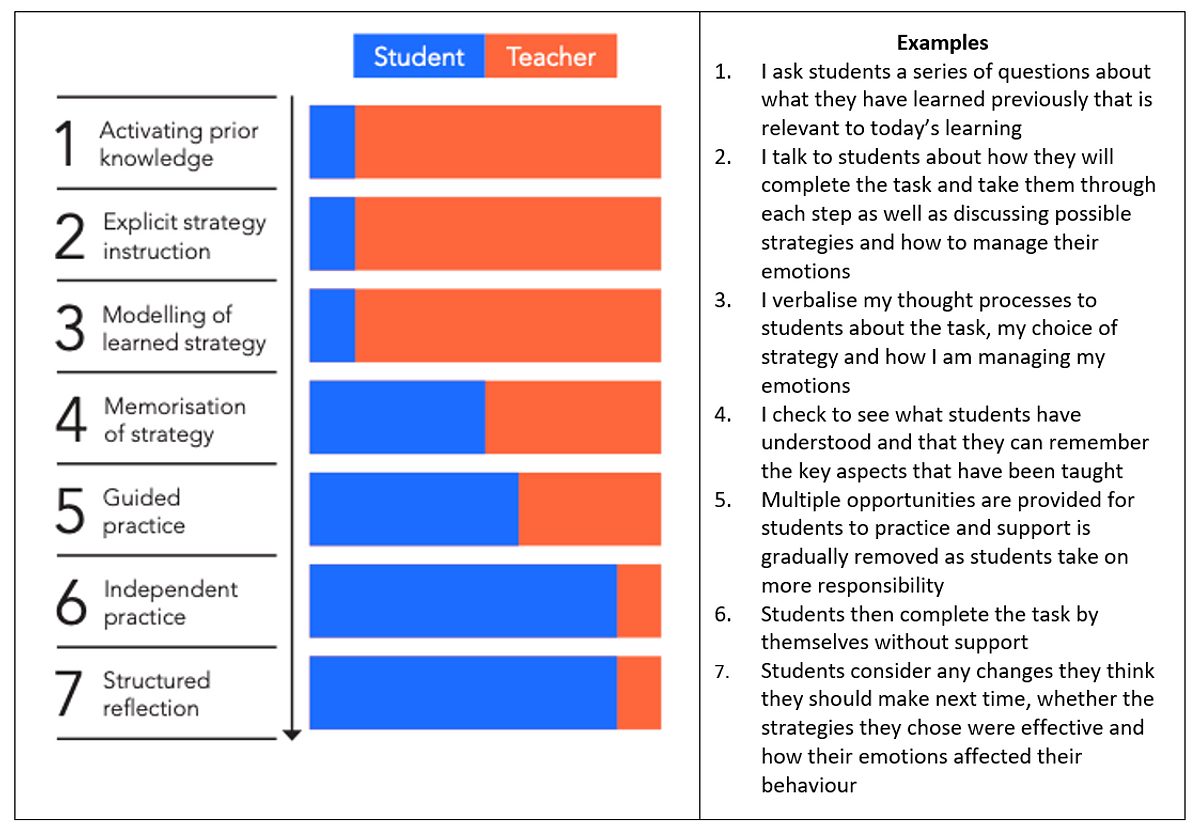

Metacognitive strategies can be broadly framed as a process of planning, monitoring, and evaluating learning. Most students will not spontaneously develop all the metacognitive strategies they need and therefore require explicit instruction. The following seven‐step model for explicitly teaching metacognitive strategies can be applied to learning different subject content at different phases and ages.

This model is useful for developing students’ independence and can provide a valuable reflective tool for teachers. Making the model visible to students and explicitly linking progression through the steps to developing their metacognitive abilities helps to make them aware of their learning. In the context of learning loss due to the pandemic, it is likely that students will progress through the steps at differing rates. This requires creativity and flexibility in the ways explicit teaching is delivered to allow students to move at their own pace and revisit content as frequently as they need.

Explicitly teach students how to manage their learning independently

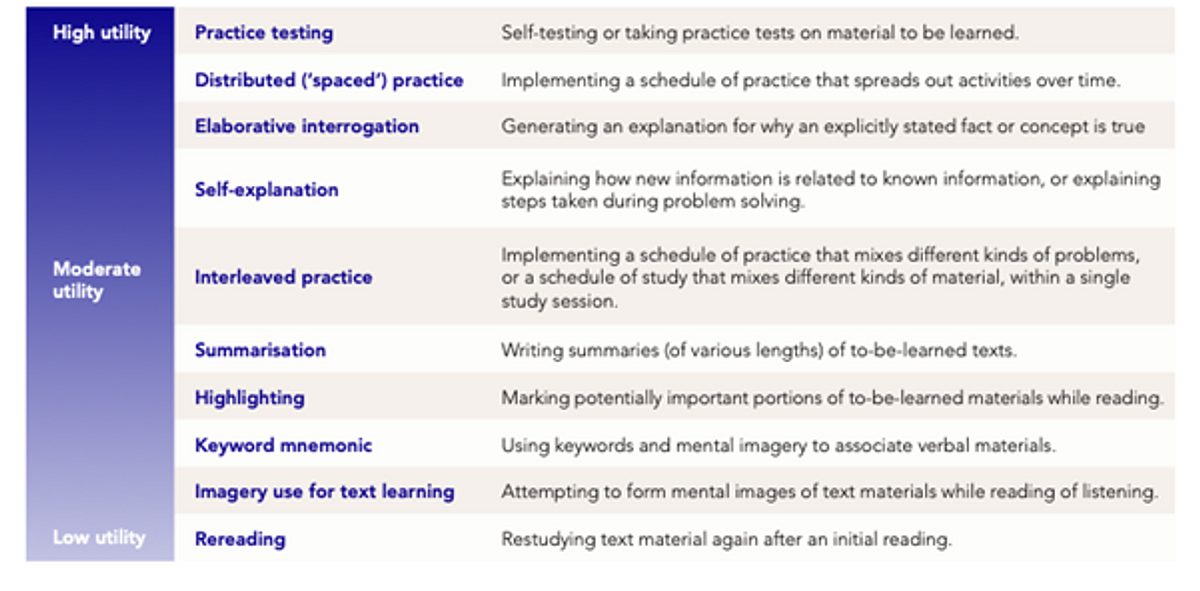

Independent learning is when students learn with a degree of autonomy, making active choices to manage and organise their learning, deploying metacognitive strategies in the process. Whilst different learning techniques are often modelled by teachers and built into the structure of learning programs, they are not all equally effective. The effectiveness of ten different learning techniques is summarised below.

The above summary is useful for stimulating discussion and challenging understanding with both teachers and students. This can be valuable to ensure that students are using precious learning time for high utility strategies, particularly if they have been impacted significantly by the pandemic and have lost ground to make up.

Putting metacognition into practice

Wodonga Senior Secondary College is a large regional school catering for 820 students in Years 10 – 12. More than 75 per cent of WSSC students are from the bottom quarter of socio-educational advantage (SEA).

Michael Rosenbrock, Assistant Principal of Wodonga Senior Secondary College explains how his school has utilised metacognitive strategies:

For more examples of metacognition in action, see the illustrations of practice from the PEARLS program.

Considerations for leaders

- Misconceptions around metacognition can hamper its implementation. Is this occurring in your context? If so, how can you effectively challenge misconceptions and build shared understanding?

- Metacognitive strategies require explicit teaching. How can the seven-step model be used to inform teaching practice in your setting? What is the best way to make this visible to students?

- Not all independent learning techniques are equal. How can you use the summary of effectiveness of learning techniques to challenge teachers and students? How can you know which low-utility practices are prevalent that may need addressing? Which high-utility practices are infrequently used that could provide significant value right now?

- The involvement of parents, carers, and families in developing metacognition can be an invaluable support for students. How could you engage parents with the effectiveness of learning techniques so that they can support their students to use their home learning time effectively? How could this help improve both parent and student agency?

Key takeaways

Developing students’ metacognition is an effective practice and is highly suited to the challenges of this time. Taking opportunities now to embed selected metacognition strategies within teaching and learning in your setting can provide meaningful benefits to student learning. Longer term impacts will require broader strategic implementation and sustained monitoring, adaptation, and support.