Practitioners, school leaders, evidence brokers, policy makers and researchers are united in our desire to get high quality research evidence into the hands of teachers – those in a position to make the biggest (in school) difference to student outcomes. However, just providing access to research evidence is not enough. Strengthening the way schools are engaged in the process of carrying out research and creating evidence, is just as important as schools using the outcomes from research.

This was a significant impetus for the Understanding School Engagement in Research (USER) study, conducted by Catholic Education Melbourne (CEM). Feedback was sought from 67 Melbourne Catholic schools through an online survey, focus groups and principal interviews, about their engagement in research projects, and engagement with research evidence. Nelson & O’Beirne (2014) argue that “the two processes [of engaging in and with research] are not mutually exclusive, and in the best examples, they complement each other (p vii).

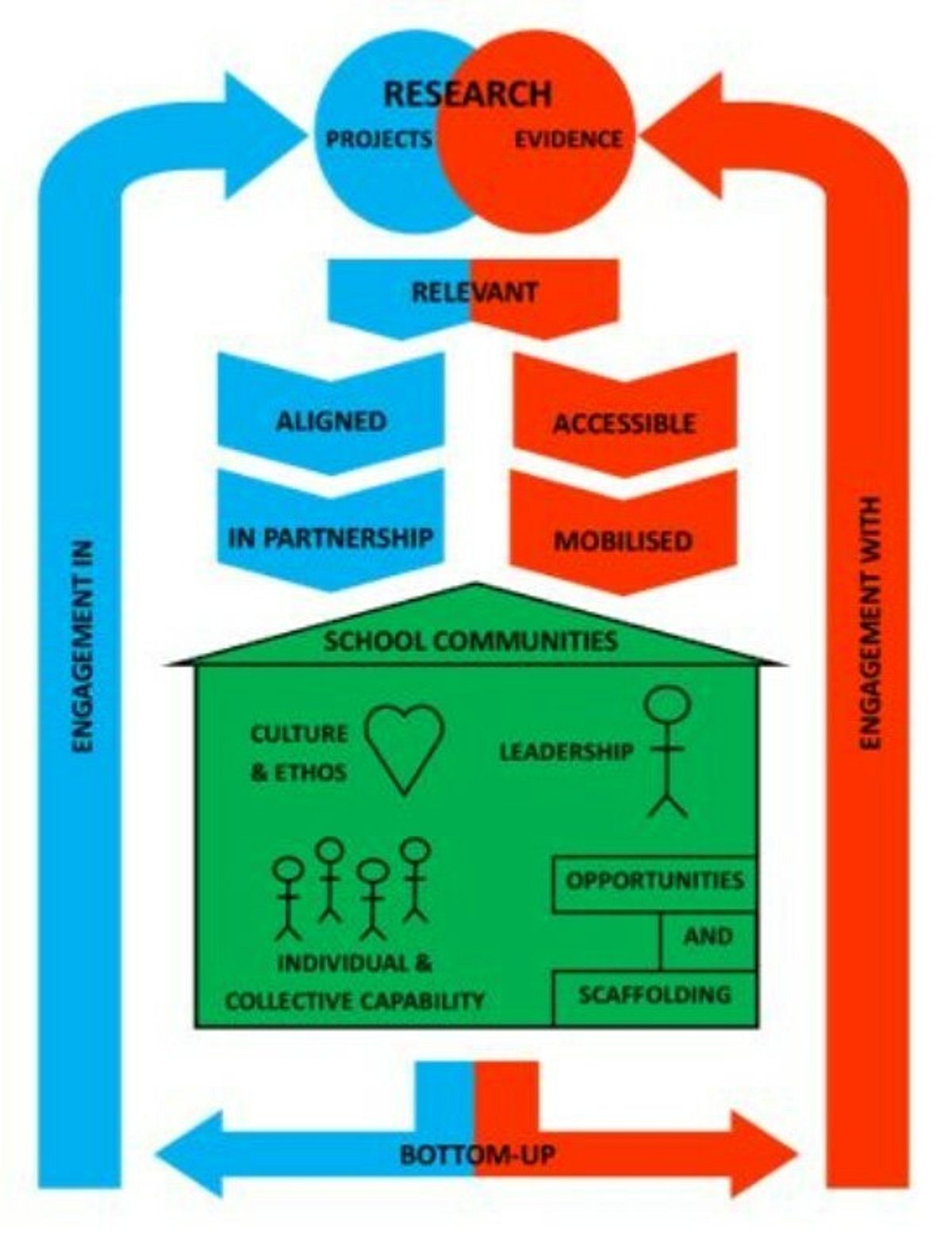

In the USER study, schools reported they are more favourable towards research projects that they deem relevant to their daily mission, are aligned to their school priorities, and are conducted ‘with’ them, not ‘to’ them.

Schools also reported that their engagement is enhanced if the research evidence is available when school staff need it, it is in a format they can understand and relate to, and staff have the capability and support to mobilise the evidence into practice.

How do the USER project findings compare to other studies on school research engagement?

CEM partnered with Associate Professor Mark Rickinson from Monash University to compare and contrast the USER project findings with the international literature, resulting in five important themes (summarised below).

1. Schools are selective about their research involvement.

Schools receive many requests to participate in academic research projects, but choose to engage in very few. In the USER study, we found schools say ‘no’ to four out of five research opportunities per year (on average). The most common reason for saying ‘yes’ is if the project is aligned with their school improvement priorities, and ‘no’ if the project demand is too great on the school in terms of time and resources required.

2. Schools are discerning about what the research is on and how it is conducted.

Not only are schools more embracing of research projects that focus on topics that are relevant to their needs, they also prefer a partnership approach, whereby staff are actively engaged in the research process and the project includes a capability building component (e.g. professional learning), not just data collection.

3. Schools access research in indirect and informal ways.

When asked where school staff access research evidence, the most common sources are through professional learning events, other colleagues and professional networks. Not only is access often indirect, engaging with research evidence tends to happen informally with their peers in conversation, planning meetings and professional learning sessions.

4. Schools value research more than they use it.

We learned through the USER study and broader literature, that while many teachers and school leaders highly value research evidence, they do not use it as much as they would like. Some barriers to using research include: limited access to evidence; formats and language that are difficult to understand and interpret; teachers not feeling confident or motivated; and limited time and opportunities to engage with research findings.

5. Schools need much more than research access.

In the education community, we tend to focus our efforts on getting research evidence into schools for teachers and leaders to use. However research engagement is much more complex! There is a lot of evidence to support regular exercise and healthy eating, yet having access to this information is often not enough to change behaviour. Dagenais et al. (2012) argue that evidence use in education is shaped by four factors: the research evidence itself; the practitioners as users; the professional and school context; and the wider system context. Targeting just one of these factors limits our capacity to really improve research engagement in schools. Focussing on all however, is where the real opportunity for improvement lies.

Understanding and improving school research engagement

A conceptual framework for understanding and improving school research engagement

The USER publication (Prendergast & Rickinson, 2019) provides greater detail on the five themes above, and also proposes a conceptual framework to make sense of the complexity and interdependent factors impacting on school research engagement. It highlights that school engagement in research, requires projects to be relevant to learning and teaching, aligned with school priorities, and conducted in partnership. Regarding school engagement with research, evidence needs to be relevant to the daily issues facing teachers and leaders, available and accessible when needed, and in formats that can be mobilised into school and classroom use. The framework also shows the school-level factors that impact on research engagement, including leadership that encourages and models the value of research, a culture of teacher collaboration and learning, and opportunities to engage in and with research.

A collective effort is required

However, strengthening school research engagement requires different thinking and practice from all key stakeholders. Researchers and research organisations should work alongside schools to develop research projects informed by actual school needs and priorities, and more actively engage schools throughout the research lifecycle. Schools should look for ways to implement supportive structures and processes that more deliberately encourage staff to engage with research findings and develop their own research capability. Jurisdictions should commission research projects that genuinely engage schools as partners, and help mobilise research findings into user-friendly outputs for school and classroom use.

There are clear policy aspirations and support from many in the education community about the role of educational research and evidence-informed practice in Australia. However, we need to know more about how research ‘lands’ in schools, how it is integrated with teaching practice, and the best ways and tools to support teachers to use research evidence. Monash University’s Q Project (Quality Use of Evidence Driving Quality Education) is a new research project that seeks to bring schools and research evidence closer to improve teaching and learning. Evidence for Learning is also working on a new project to investigate the mobilisation of research evidence in schools.

These projects will help build our understanding of school engagement with research, but the real opportunity for change lies in the daily efforts of Australian educational researchers, schools, jurisdictions and evidence brokers working together.

Further information on the Understanding School Engagement in and with Research study, as well as resources on school research engagement can be found here, or email Shani Prendergast, Senior Research Analyst at Catholic Education Melbourne, sprendergast@cem.edu.au.

References

Dagenais, C., Lysenko, L, Abramai, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Ramde, J. & Janosz, M. (2012). Use of research-based information by school practitioners and determinants of use: a review of empirical research. Evidence & Policy, 8(3), 285 – 309.

Dimmock, C. (2016) Conceptualising the research – practice – professional development nexus: mobilising schools as ‘research-engaged’ professional learning communities. Professional Development in Education, 42(1), 36 – 53.

Nelson, J. and O’Beirne, C. (2014). Using Evidence in the Classroom: What Works and Why? Slough: National Foundation for Educational Research.

Prendergast, S., & Rickinson, M. (2019). Understanding school engagement in and with research.Australian Educational Researcher, 46(1), 17 – 39.