This is the third in a series of posts addressing some reservations about the validity and usefulness of meta-analyses in education. I started writing these posts after reading a thoughtful piece from Dr Deb Netolicky outlining some of her concerns with Evidence for Learning’s Teaching & Learning Toolkit (the Toolkit).

For further background, you can read the other two posts, covering concerns about how schools might approach the Toolkit and whether meta-analysis oversimplifies and loses context from the underlying studies, Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

This post addresses two final concerns:

- Meta-analysis may include studies of poor quality, which affects the quality of conclusions drawn; and

- Meta-analysis focusing on academic outcomes can ignore the broader goals of education beyond academic achievement.

This is the third in a series of posts addressing some reservations about the validity and usefulness of meta-analyses in education. I started writing these posts after reading a thoughtful piece from Dr Deb Netolicky outlining some of her concerns with Evidence for Learning’s Teaching & Learning Toolkit (the Toolkit).

For further background, you can read the other two posts, covering concerns about how schools might approach the Toolkit and whether meta-analysis oversimplifies and loses context from the underlying studies, Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

This post addresses two final concerns:

- Meta-analysis may include studies of poor quality, which affects the quality of conclusions drawn; and

- Meta-analysis focusing on academic outcomes can ignore the broader goals of education beyond academic achievement.

In her post, Deb notes that Snook et al (2009) ‘point out that any meta-analysis that does not exclude poor or inadequate studies is misleading or potentially damaging.’ Evidence for Learning agrees with this statement.

In a blog titled ‘On Meta-Analysis: Eight Great Tomatoes’ Bob Slavin, Director of the Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University, makes a similar point and gives examples of what might make a study, to use Snook’s language,‘poor or inadequate’:

In her post, Deb notes that Snook et al (2009) ‘point out that any meta-analysis that does not exclude poor or inadequate studies is misleading or potentially damaging.’ Evidence for Learning agrees with this statement.

In a blog titled ‘On Meta-Analysis: Eight Great Tomatoes’ Bob Slavin, Director of the Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University, makes a similar point and gives examples of what might make a study, to use Snook’s language,‘poor or inadequate’:

One challenge when applying this type of screening to a meta-analysis is the limited evidence base that currently exists in education. On some topics where teachers want good research evidence, there aren’t many rigorous studies to include.

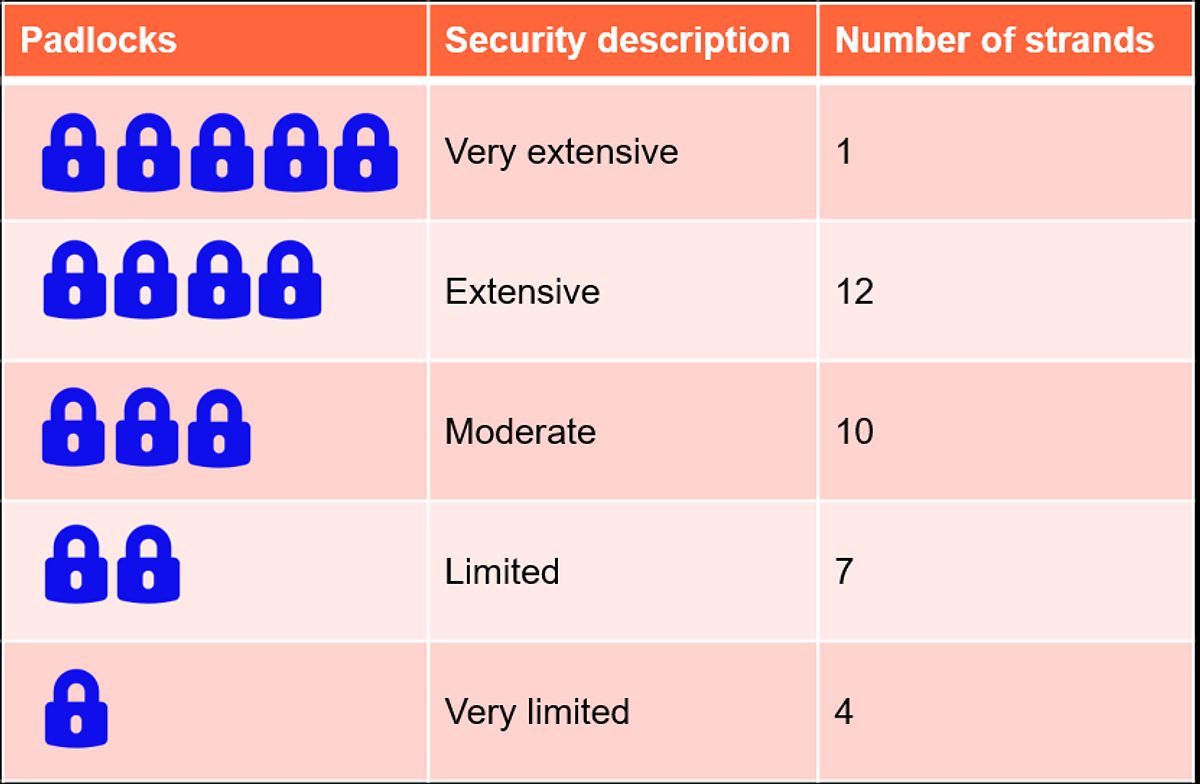

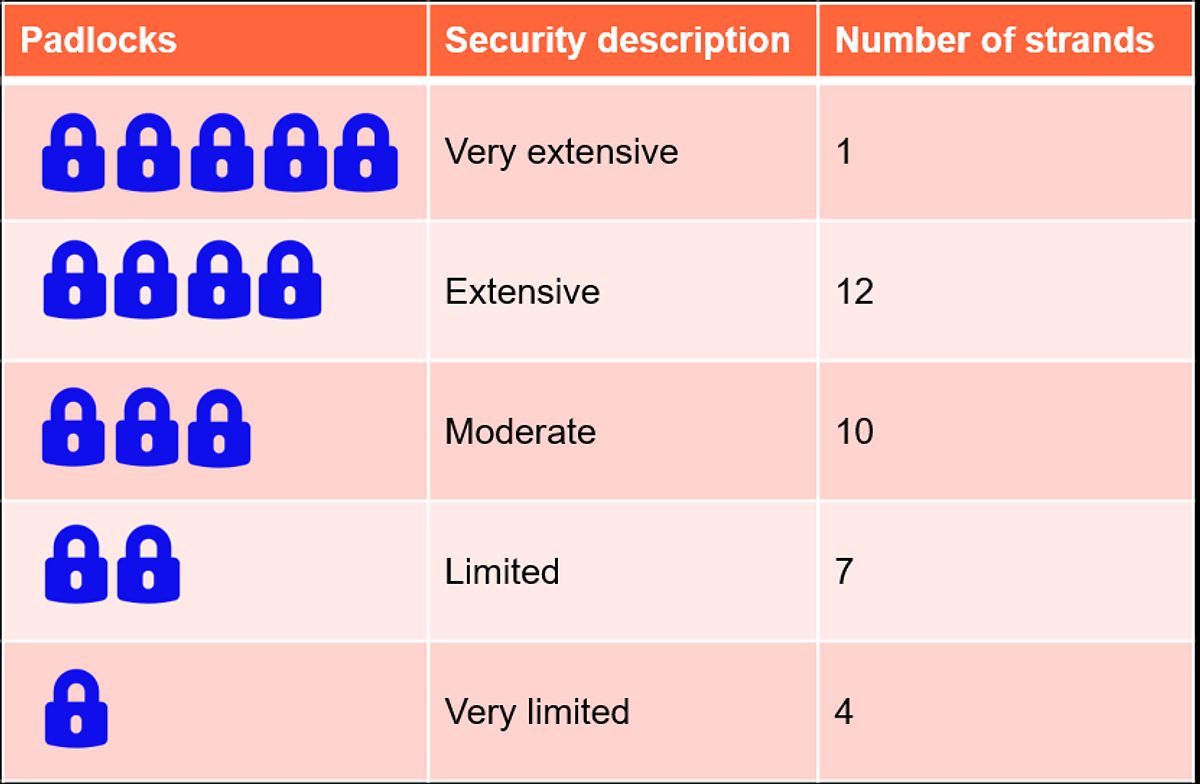

To be useful to teachers while still maintaining high standards of quality for inclusion, the Toolkit’s padlock rating system tries to make the criteria for including studies transparent, while acknowledging some limitations in the evidence base. The padlock ratings, as shown in the evidence security table, reflect not just the quantity of studies for a given Toolkit strand, but also their quality. So, for instance, a strand with only one padlock is based on ‘[q]uantitative evidence of impact from single studies, but with effect size data reported or calculable. No systematic reviews with quantitative data or meta-analyses located,’ while a strand with five padlocks is based on ‘[c]onsistent high quality evidence from at least five robust and recent meta-analyses where the majority of the included studies have good ecological validity and where the outcome measures include curriculum measures or standardised tests in school subject areas.’ (Section 4 of the Toolkit’s Technical Appendices provide much more detail for those interested. See especially the sections on (1) ‘Super-synthesis’, (2) Search and inclusion criteria, (3) Estimating overall impact, and (4) Weight of evidence and quality assessment, beginning on page 11.)

So, where there is limited but still potentially useful evidence, the Toolkit’s padlock system makes that transparent for school leaders and teachers. Where there is extensive high-quality evidence, the padlock system makes that clear, too. To return to the analogy of climbing a cliff from Part 2, the padlocks help to understand not only how many climbers have taken a particular route before, but the quality of report they have given about how to navigate it.

The table below shows the current number of strands in the Toolkit at each level of evidence security. As more rigorous education studies are published, the security of the evidence base improves and the Toolkit is updated to reflect this.

Table 1: Strands in the Toolkit at each level of evidence security

One challenge when applying this type of screening to a meta-analysis is the limited evidence base that currently exists in education. On some topics where teachers want good research evidence, there aren’t many rigorous studies to include.

To be useful to teachers while still maintaining high standards of quality for inclusion, the Toolkit’s padlock rating system tries to make the criteria for including studies transparent, while acknowledging some limitations in the evidence base. The padlock ratings, as shown in the evidence security table, reflect not just the quantity of studies for a given Toolkit strand, but also their quality. So, for instance, a strand with only one padlock is based on ‘[q]uantitative evidence of impact from single studies, but with effect size data reported or calculable. No systematic reviews with quantitative data or meta-analyses located,’ while a strand with five padlocks is based on ‘[c]onsistent high quality evidence from at least five robust and recent meta-analyses where the majority of the included studies have good ecological validity and where the outcome measures include curriculum measures or standardised tests in school subject areas.’ (Section 4 of the Toolkit’s Technical Appendices provide much more detail for those interested. See especially the sections on (1) ‘Super-synthesis’, (2) Search and inclusion criteria, (3) Estimating overall impact, and (4) Weight of evidence and quality assessment, beginning on page 11.)

So, where there is limited but still potentially useful evidence, the Toolkit’s padlock system makes that transparent for school leaders and teachers. Where there is extensive high-quality evidence, the padlock system makes that clear, too. To return to the analogy of climbing a cliff from Part 2, the padlocks help to understand not only how many climbers have taken a particular route before, but the quality of report they have given about how to navigate it.

The table below shows the current number of strands in the Toolkit at each level of evidence security. As more rigorous education studies are published, the security of the evidence base improves and the Toolkit is updated to reflect this.

Table 1: Strands in the Toolkit at each level of evidence security

Deb’s post also says, ‘Terhart (2011) points out that by focusing on quantifiable measures of student performance, meta-analyses ignore the broader goals of education.’ With former teachers and parents within E4L, we recognise the importance of aspects of education that cannot be measured. How children’s teachers connect with them and inspire them, how they stimulate their curiosity and how they shape their ethical understanding to help them develop as active citizens; these are all important. From our point of view, it would be more accurate to say that meta-analyses focus on the quantifiable elements of a well-rounded education. E4L believes academic achievement and other quantifiable measures are also an important part of teachers’ and schools’ core work and hope that judicious use of the Toolkit can help them in that.

Deb’s post also says, ‘Terhart (2011) points out that by focusing on quantifiable measures of student performance, meta-analyses ignore the broader goals of education.’ With former teachers and parents within E4L, we recognise the importance of aspects of education that cannot be measured. How children’s teachers connect with them and inspire them, how they stimulate their curiosity and how they shape their ethical understanding to help them develop as active citizens; these are all important. From our point of view, it would be more accurate to say that meta-analyses focus on the quantifiable elements of a well-rounded education. E4L believes academic achievement and other quantifiable measures are also an important part of teachers’ and schools’ core work and hope that judicious use of the Toolkit can help them in that.

In the introduction to his 2013 paper, ‘Building Evidence into Education,’ Ben Goldacre writes;

In the introduction to his 2013 paper, ‘Building Evidence into Education,’ Ben Goldacre writes;

I feel it’s worth quoting Goldacre further about creating a professional culture where reference to rigorous evidence is the norm:

‘This is not an unusual idea. Medicine has leapt forward with evidence-based practice, because it’s only by conducting ‘randomised trials’ – fair tests, comparing one treatment against another – that we’ve been able to find out what works best. Outcomes for patients have improved as a result, through thousands of tiny steps forward. But these gains haven’t been won simply by doing a few individual trials, on a few single topics, in a few hospitals here and there. A change of culture was also required, with more education about evidence for medics, and whole new systems to run trials as a matter of routine, to identify questions that matter to practitioners, to gather evidence on what works best, and then, crucially, to get it read, understood, and put into practice.

‘There are many differences between medicine and teaching, but they also have a lot in common. Both involve craft and personal expertise, learnt over years of experience. Both work best when we learn from the experiences of others, and what worked best for them. Every child is different, of course, and every patient is different too; but we are all similar enough that research can help find out which interventions will work best overall, and which strategies should be tried first, second or third, to help everyone achieve the best outcome.’

We hope that the Toolkit, and the meta-analyses that underpin it, can be part of the culture shift that Goldacre outlines. If it’s used as a blunt instrument to tell teachers what to do, the Toolkit will no doubt have detrimental effects. But if teachers and school leaders use it to inform their decisions with better evidence, we hope that it will help improve education for students, right across Australia.

I feel it’s worth quoting Goldacre further about creating a professional culture where reference to rigorous evidence is the norm:

‘This is not an unusual idea. Medicine has leapt forward with evidence-based practice, because it’s only by conducting ‘randomised trials’ – fair tests, comparing one treatment against another – that we’ve been able to find out what works best. Outcomes for patients have improved as a result, through thousands of tiny steps forward. But these gains haven’t been won simply by doing a few individual trials, on a few single topics, in a few hospitals here and there. A change of culture was also required, with more education about evidence for medics, and whole new systems to run trials as a matter of routine, to identify questions that matter to practitioners, to gather evidence on what works best, and then, crucially, to get it read, understood, and put into practice.

‘There are many differences between medicine and teaching, but they also have a lot in common. Both involve craft and personal expertise, learnt over years of experience. Both work best when we learn from the experiences of others, and what worked best for them. Every child is different, of course, and every patient is different too; but we are all similar enough that research can help find out which interventions will work best overall, and which strategies should be tried first, second or third, to help everyone achieve the best outcome.’

We hope that the Toolkit, and the meta-analyses that underpin it, can be part of the culture shift that Goldacre outlines. If it’s used as a blunt instrument to tell teachers what to do, the Toolkit will no doubt have detrimental effects. But if teachers and school leaders use it to inform their decisions with better evidence, we hope that it will help improve education for students, right across Australia.

Responding to reservations about meta-analyses: Part 1.

Responding to reservations about meta-analyses: Part 2.

John Bush is the Associate Director of Education at Social Ventures Australia and part of the leadership team of Evidence for Learning. In this role, he manages the Learning Impact Fund, a new fund building rigorous evidence about Australian educational programs.

Responding to reservations about meta-analyses: Part 1.

Responding to reservations about meta-analyses: Part 2.

John Bush is the Associate Director of Education at Social Ventures Australia and part of the leadership team of Evidence for Learning. In this role, he manages the Learning Impact Fund, a new fund building rigorous evidence about Australian educational programs.